Three weeks ago we published preliminary results of data analysis of the honeypot for the Telnet protocol, which we have launched in test mode. Today we will look at the situation change after we installed the tool on all the Turris routers.

On the afternoon of June 9, all the routers’ Turris OS was updated to version 2.3 and “minipots” for Telnet installed. Minipots simulate an existing service, while actually writing a log file on attacker’s attempts to connect.

Although Telnet is a service that has been long outdated by SSH, we could not rule out the possibility someone might want to rightfully use it. That is why we have by default set up the minipot to collect attackers’ addresses only and made the collection of the attempted login information an option. After all, there was still a risk of gathering a password from a person who commonly uses the service.

Along with the router update, we have sent an e-mail to all users with the instruction on how to turn on name and password collection for us to gather as much relevant information as possible. To date, 263 users have turned it on, for which we are very grateful. Thanks to them, we were able to increase the number of active probes about 40 times and to detect a much greater number of attacks.

A home router botnet

In the previous post I described a curious similarity between attackers in terms of the login names and passwords they use. A group of attackers who used nontrivial passwords like “J8UbVc5430” or “biyshs9eq” was especially interesting. At that time, it had 121 unique IP addresses, which, according to our analysis, for the most part belonged to ASUS home routers.

What does this group look like now? It has definitely expanded. It now includes more than 7000 unique IP addresses and the composition of devices remains roughly the same – it still concerns mainly ASUS home routers.

Another curious fact is that from all the detected Telnet attacks, ASUS devices mostly (with the exception of a few percent) belonged to this group of attackers.

We naturally tried to gather more information about this possible botnet. With the help of CSIRT.CZ, we contacted Czech providers who had several infected routers in their networks and we also prepared our own trap for the attackers. In addition to a commonly attacked router model we purchased to monitor its condition on the Internet, we also prepared two fully functional honeypots for Telnet, where we hope to catch the attackers. One of them is password-free and the other is secured by one of the strong passwords from the attackers’ list.

For now, we have had only partial success. We were lucky to detect the activity of two attackers from the mentioned group in one of the honeypots. Unfortunately, the commands they tried were not as interesting; they just tested the connection and apparently added the router to their attackable router list for later use.

The results of the device accessibility analysis in this botnet were also curious. A considerable number of the routers had an accessible web interface, network printer interface, UPnP or DNS resolver. Given the setting of these devices, it is probable that the user have completely disabled their firewall. As in these cases the web interface becomes accessible from the outer network and the default login is admin/admin, it is possible that this was the attack vector. However, these devices contain other vulnerabilities as well.

How big is the botnet?

Because of limited time and number of probes we don’t know the size of the botnet yet, because we haven’t been “visited” by all members so far. The speed of new IP addresses in the mentioned group coming up decreases over time, despite the fact that the number of active probes has been mildly increasing. We can use this for a very rough estimate of the overall number of botnet devices. If we suppose that the speed trend of the increase in recorded new IP addresses in the botnet continues in the following days, we can estimate the moment when this speed will reach zero. From this value we can then calculate the overall botnet size. According to the data available at this moment we would be talking about some 12 thousand devices. This estimate, however, is burdened with a considerable error and the method fails to take into account the gradual expansion of the botnet as it attacks more devices. The actual size of the botnet is probably bigger.

We’ll be monitoring the situation and provide information if we learn more about the botnet.

The Turkish botnet

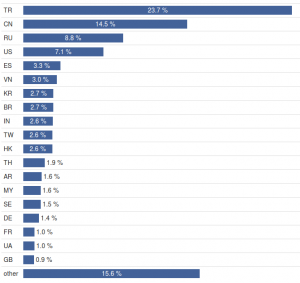

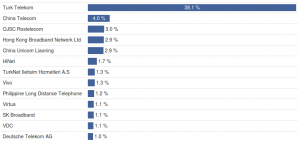

Apart from the chance to identify similar attacker groups it is also interesting to monitor the overall Telnet attack situation. The following figure shows the shares of individual countries on the number of attacks.

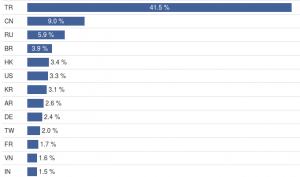

It is interesting to note that Turkey has a very high (almost 24 %) share in this list, although this country is usually not very active in network attacks. When we analyze groups of similar attackers, we find one with more than 80% share of Turkish attackers. It is by far the biggest group with more than 12 thousand members, where 40 % of IP addresses is Turkish. Moreover, more than 90 % of those addresses belong to one provider, Türk Telekom.

We can only speculate about the causes of this development. Unfortunately device monoculture, which is typical for big providers, might make these devices susceptible to mass attacks, if someone discovers a vulnerability that can be abused. It is possible that this is what happened in this case.

What next?

The results we present in this article are based on just a few days of running our Telnet minipots. Despite this I believe them to be of interest. We will be monitoring the situation, search for new information and try to bring this research to its end which would be the remedy of the situation. Together with CSIRT.CZ we have started to inform the Czech ISP and foreign partners and we are looking forward to any responses. Especially communication with the Turkish Telekom might be very interesting.

Finally, I’d like to once again thank all of our uses who are helping us with this research. And I’d like to ask everyone, whether they’re using Turris or not, to be careful. If nothing else, try to scan your IP address in one of the publicly available port scanners. What if you have open services you don’t know about?